An antiques dealer friend generally buys and sells “mid-century” furniture, which doesn’t interest me very much since I was making furniture “back then.” However, she finds some interesting items. Recently, she asked me to re-glue two chairs she had gotten. She told me they were button-back Hitchcocks. When I saw them, I realized she was correct. But, there was more to this story.

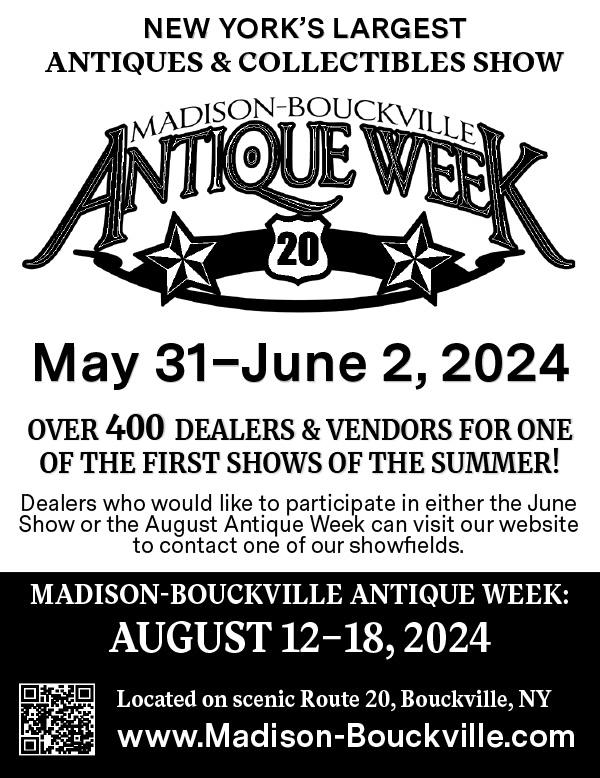

Stenciled across the lower surface of the back slat was “Ethan Allen * Button Back Hitchcock” (see photo). Although there were several other things that “told” me these weren’t chairs made by the Hitchcock company, that stencil was all I needed to see. Ethan Allen manufactured these Hitchcock STYLE chairs. She was hoping they were authentic, despite the stenciled line.

This picture shows how the top of the real rush seat was protected when the hair was spray painted black.

It turns out that Ethan Allen could use the word “Hitchcock” since it now is a generic word, not protected. Also, Hitchcock and others from his time who made such chairs stenciled the name on the rear seat strip. The exception was when the name was on a high back rocker, such as a Boston type. Then, the name was stenciled on the top slat, which was easier to see.

Without that stencil, some of the other “red flags” were the domed plugs in the screw holes where screws were holding the chairs together (see photo). If this had been a real Hitchcock chair, there wouldn’t have been screws there to create holes to fill. Most of the early Hitchcock chairs with rush seats had mortise and tenon joints where the seats met the legs. Also, the bottoms of the seats showed where the rush had been masked off so the chair could be spray painted after the seat had been put in (see photo).

I was asked to examine a flip-top or bench table for a customer who was interested in it for her family room. It was made from pine and in an old “natural” honey-colored finish. I first saw it set up as a table. It looked good. The bottoms of the feet had a little damage. That’s all right, usually indicating some age. When I tipped the top up to form the bench, I saw a problem. The top was made from three rather wide boards. However, where two boards joined I saw evidence of there having once been a latch or something. This caused me to examine the top much more closely. The top was wood that once had been used as a barn door or something like that.

The bottom of the piece was well made. The seat was dovetailed into the sides and the bottom of each side was nicely cut out to form good-looking feet. However, the cleats under the top had been nailed into place. The woodworker who made the base should have crafted the top as well. If he had, I would have expected him to cut dovetail grooves in the underside of the top to insert the cleats. Also, the top and base woods were different in thickness. They wouldn’t have to have been the same. But, the top was much thicker. It was my feeling that the top was made by a different person, years after the base had been crafted. This is understandable because tops often were damaged due to fire, excess cutting of meat, or other reasons. However, my customer had been told the table was authentic and very old. Needless to say, she did not buy this “marriage.”

The table was a made-up piece, not by the seller, but done a few years earlier. That’s fine. A good-looking base was saved. However, it should have been being sold that way for a lower price. As for age, there’s a lot of guesswork involved. I looked at the nails. The ones in this piece could have been from any time between about 1800 to the late 1800s. It’s a country piece. Country cabinetmakers didn’t have the most up-to-date hardware. When I was a child, I remember my grandfather showing me “old nails” that he used to hold things together. They were leftovers from an earlier time. This was in the late 1930s. Dating country pieces can be tricky. Be careful!

This photo shows the stenciled line on the back of this Ethan Allen reproduction Hitchcock.

Sometimes when looking at a piece of furniture, it’s difficult to know whether it’s “right” or has had some alterations or work done. Recently, at an auction house, I was checking an “18th century chest of drawers” for a client. It was tough to get a good look because of the way the furniture was arranged. Since I was alone, I couldn’t get to see the rear of the case. But, I saw enough to talk my customer out of bidding on that chest.

It looked good from the floor. However, getting close “told” a different story. When I looked at a drawer side, I could see wood worm galleries or channels. This meant the sides either had been replaced or heavily sanded. Why? They showed wear on the bottoms, which didn’t match the slides they moved on. This was the same with all the drawers. There was a lot of wear and tear on the drawer fronts and the bracket feet. From a distance, this looked more or less normal. However, close up, I could see that all of the scratches seemed to have been made by the same item. All went in the same direction with what appeared to be about the same force. These marks were fake.

Although the chest was advertised as 18th century, it had hardware that didn’t look that old. The pulls seemed to be original or at least used the original post holes. But, they just didn’t seem “right” for this piece. I don’t know what the history was on the chest. However, the item was not what it was being auctioned as. I stayed for the auction – someone paid a fairly high price to take it home. You can’t be too careful, especially at an auction. Although most items are as they are sold, some are not. And, generally, you have no recourse if you buy something that’s been faked.

Many pieces I see, particularly in co-ops, aren’t fake, just mislabeled, usually with the wrong date or period. When I point this out, I generally get, “Well, it’s over a hundred years old!” Most people who know me know I don’t consider that antique, at least not when referring to furniture. In 1917, 100 years ago, most furniture was factory-made. I, along with lots of other serious “antique people,” consider furniture made before 1830-1850 to be antique. Of course, everyone has the right to decide what he or she thinks is an antique.

One thing I see a lot is chests of drawers dated “early 1800s” that aren’t. All you need to do is pull out a drawer to look at how the sides are secured to the fronts. Machine-made dovetails came into use in the mid-1800s. Mostly, they were used in factory-made pieces. Usually the manufacturers were in or near large cities. Country cabinetmakers cut their own dovetails until the late 1800s. Some makers of reproduction antique furniture still cut dovetails by hand, as do I when I’m restoring a period piece. There are two things of note here: if the dovetails are machine cut, the piece probably dates from the late 1800s. And, because an item has hand-cut dovetails doesn’t prove it dates from the early 1800s. Always check more than one detail when trying to date furniture.

Some factory-made furniture has nails holding the drawer sides to the fronts. Mostly, the nails are round-headed and date from about 1900. But, if you see a rather rough, simple piece with a drawer, the sides might be nailed in place with 18th century cut nails. Untrained woodworkers often didn’t cut the dovetails, either because they didn’t know how or didn’t want to take the time. Instead, they used a couple of old nails to hold a drawer together, something my grandfather would have done in the ‘30s. This isn’t common, but was done.

In this photo you clearly an see the “button” hiding a screw, proving this chair is held together by screws. On an authentic Hitchcock chair, this joint would have been mortice and tenon.

To help establish age, look at the underside of a drawer. If the bottom is thin and cut with modern power tools, that should “tell” you a lot. Also, check the way the bottom is shaped to fit into the sides. If the bottom is thick and hand-chamfered to fit dadoes in the sides, there’s a good chance the drawer is old and a true antique. However, if the bottom is thick and the edges are cut out with a power saw to fit into the dadoes, the drawer was made after the mid-1800s.

One of my customers called to ask me to tighten a Hepplewhite tripod candle stand she and her husband had found in an antiques shop in New England this past summer. When they brought it, I told them it was a Hepplewhite-style stand, not of the period. Since they paid a lot for it and were told it was period, they wanted to know why I said that by just looking while it still was in their car.

What I noticed was that the legs had been doweled to the baluster or pedestal. If it had been of the period, the legs would have been dovetailed into the bottom of the turning. Also, the pedestal was heavy, especially when compared to a true Hepplewhite baluster. Instead of 1790 or so, the stand dated from between 1870 and 1900. That only is a guess since there have been many copies of this type of stand reproduced, even still today. Except for being a little heavy, the stand was good-looking. They learned a lesson on how to look at this type of table or stand.

As always, it’s in the details and knowing what you’re looking for and at when examining antique furniture!

Next month, we’ll look at more fakes I’ve known.